I met Cicero, an elder of the Quw’utsun’ tribe, as he was carving a totem out of a cedar trunk. His totem, inspired by a tribal story, showed a colorful thunderbird with angular wings holding a killer whale in his claws. The black and white spotted killer whale holds a chinook salmon between his fins. As he was carving, Cicero told me the story of his totem.

One summer a very long time ago, no more chinook salmon were swimming up the Cowichan River. The chief of Quw’ustun’ clan, worried about the survival of his tribe, decided to send two of his bravest men to the mouth of the river to report back what had happened to the salmon. When the two men arrived after many days of running, they saw a gigantic killer whale eating all the salmon that were desperately trying to reach the fresh water of the Cowichan River. They returned to the village, still shaking from fear, and told their Chief what they had witnessed. After meditating on the problem for several days, the Chief decided that the tribe should invoke the Thunderbird for help. A three-day-long singing and dancing ceremony was organized, bodies were painted, and one could feel the soil of the Earth vibrating from the forceful dancing miles away. Through the clouds, the Thunderbird finally came down, opened his claws, and grabbed the killer whale out of the water to drop him on top the nearest mountain. Every summer since then, chinook salmon have found their way into the Cowichan valley. And every year Cicero goes spear fishing.

After finishing the story, Cicero paused and fell silent. I broke the silence by asking what he uses to paint the figures of his totem. He responded that his ancestors used to extract pigments from plants that would then be mixed with seal fat to create a resistant oil paint, but that today almost all carvers use acrylics, which are cheaper and easier to use. As for the wood used for the totem, Cicero used to just cut down the appropriate tree in the forest, but now laws oblige him to buy each tree from a local company that sells them at five thousand dollars a piece.

According to Hwiemtum, the tribe cultural representative, children should by the age of twelve be able to survive in the forest for five or six days on their own. But because of the modern world in which they grow up, they generally have no interest in cultivating those skills, often considered backwards. While there are more than 177 indigenous dialects in British Columbia, they are usually only spoken by the elders of the tribe. Out of the four thousand aboriginals that form the Quw’ustun’ tribe, only 6% can fluently speak the native tongue, Hul’qumi’num. Recently, some federal elementary schools have started to incorporate native language instruction into their curriculum for all students, asking elders to facilitate the instruction. The problem, however, is that these elders do not have formal training to teach. Furthermore, this spoken language has recently been given a written form, with which not all elders are familiar.

The Hul’qumi’num language is key for the culture to survive; it is used in most of the tribe’s ceremonies and it reflects the essence of the view with which the tribe members look at the world we live in. They do not have a word for months to express a certain period of the year but instead use words that describe changing natural processes such as the upstream migration of the chinook salmon in the Cowichan River. They also use the Hul’qumi’num language when they interact with plants and animals of the forests. I remember Hwiemtun once presenting himself to a red cedar tree as we were walking through the forest. He thanked him for being here and told him he would take some of his bark to make a cedar hat. He then made an offering of tobacco and started pulling off some of the tree’s bark. He explained that it was better to do this in the morning at the end of spring when the tree can easily heal.

Hwiemtun told some traumatizing stories of his school experience. He recalled a day when the police and a priest, who also was his teacher, came to the house of his grandmother to threaten his entire family, forbidding them from using their native language. While Hwiemtun attended day schools, many of his older friends from the tribe attended boarding schools. Aboriginal students would be taken away from their families for the whole academic year and forced to adopt Western culture through an abusive education system. The last of these schools was closed in 1996.

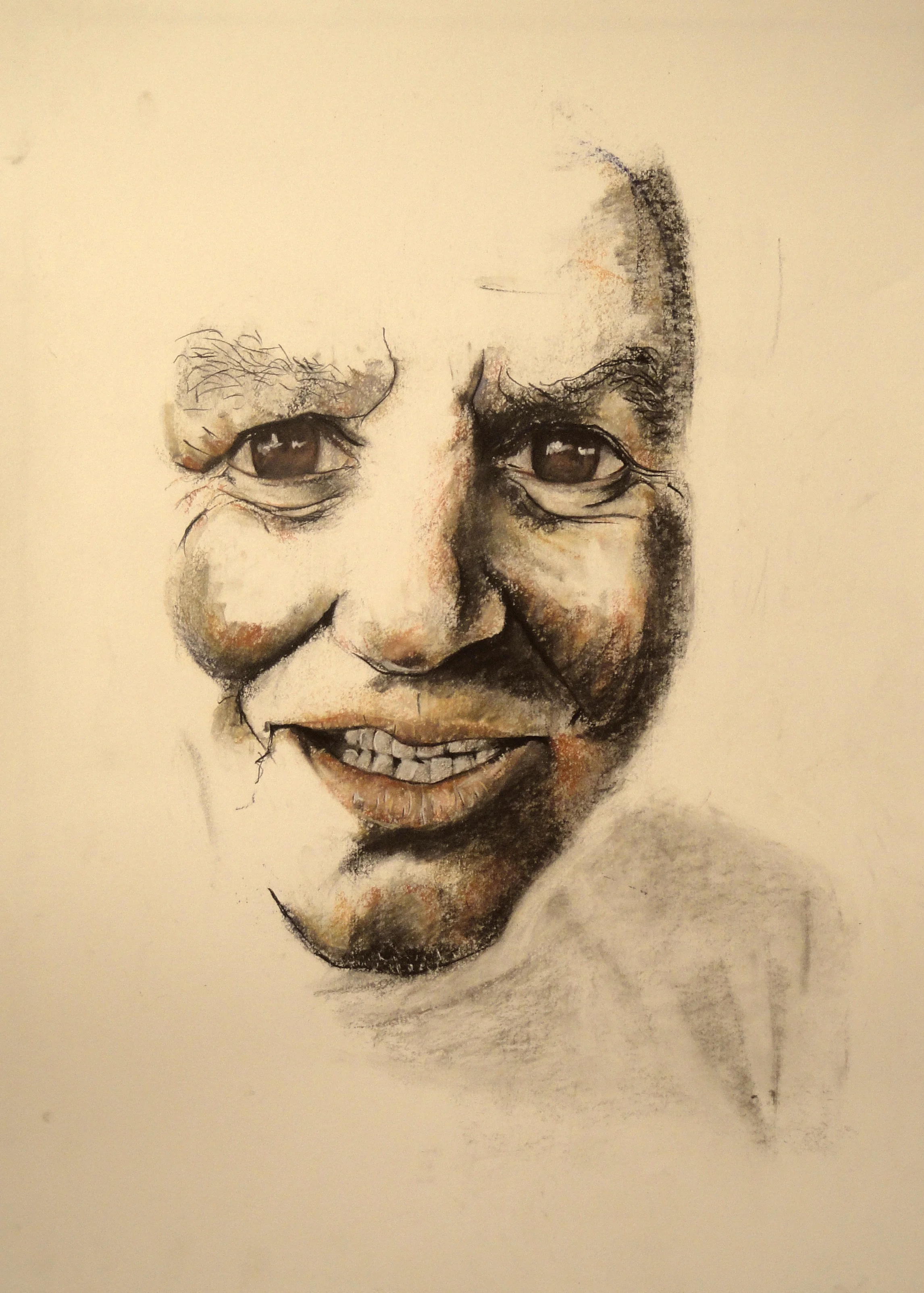

A week later, at the annual war canoe races that take place in the Cowichan Bay, I met with an elderly woman who is an elder of the Quw’ustun’ tribe. She used to participate in those races, and proudly told me that her team had won 27 years in a row. They would practice every day throughout the year for this special occasion at which many of the aboriginal tribes from the North American West Coast get together and compete on the water. Each canoe is carved out of a single piece of red cedar trunk and painted according to the family’s colors. Her family’s canoe was decorated with a blue stripe on top of a white stripe. To my surprise, teams of 10-year-old children were enthusiastically participating in five-mile races in the cold and windy water of the Salish Sea.

I was invited to join the family for lunch and I learnt that three of the members had committed suicide over the last couple of months. Alcohol, drugs, and low employment rates are important factors in the very high suicide rates among the Quw’utsun’ tribe. Perhaps more important is the destabilization process indigenous people are going through, and the loss of their cultural identity in an increasing modernized world is pushing them to their demise. Not only are they forced daily into Western culture through education, employment, and federal regulations, but they also face high levels of racism. The elderly woman I was talking to told me how she would be verbally abused by other customers as she was buying food with her handicapped mother.

Each tribe has their own specific funeral ceremonies depending on their stories and beliefs. In the Quw’utsun’ tribe, when a person dies, their favorite food and clothes are placed on a wooden table which is then burned to ashes. The process gives an opportunity for the spirit of the person to prepare itself for their travels. The Shaker’s Church, a combination of American Indian, Catholic, and Protestant beliefs and practices, plays an important ceremonial and spiritual role for many aboriginal tribes in British Columbia. According to the elder women, Shaker’s Church practices are slowly shifting away from Christianity towards a stronger integration of native practices.

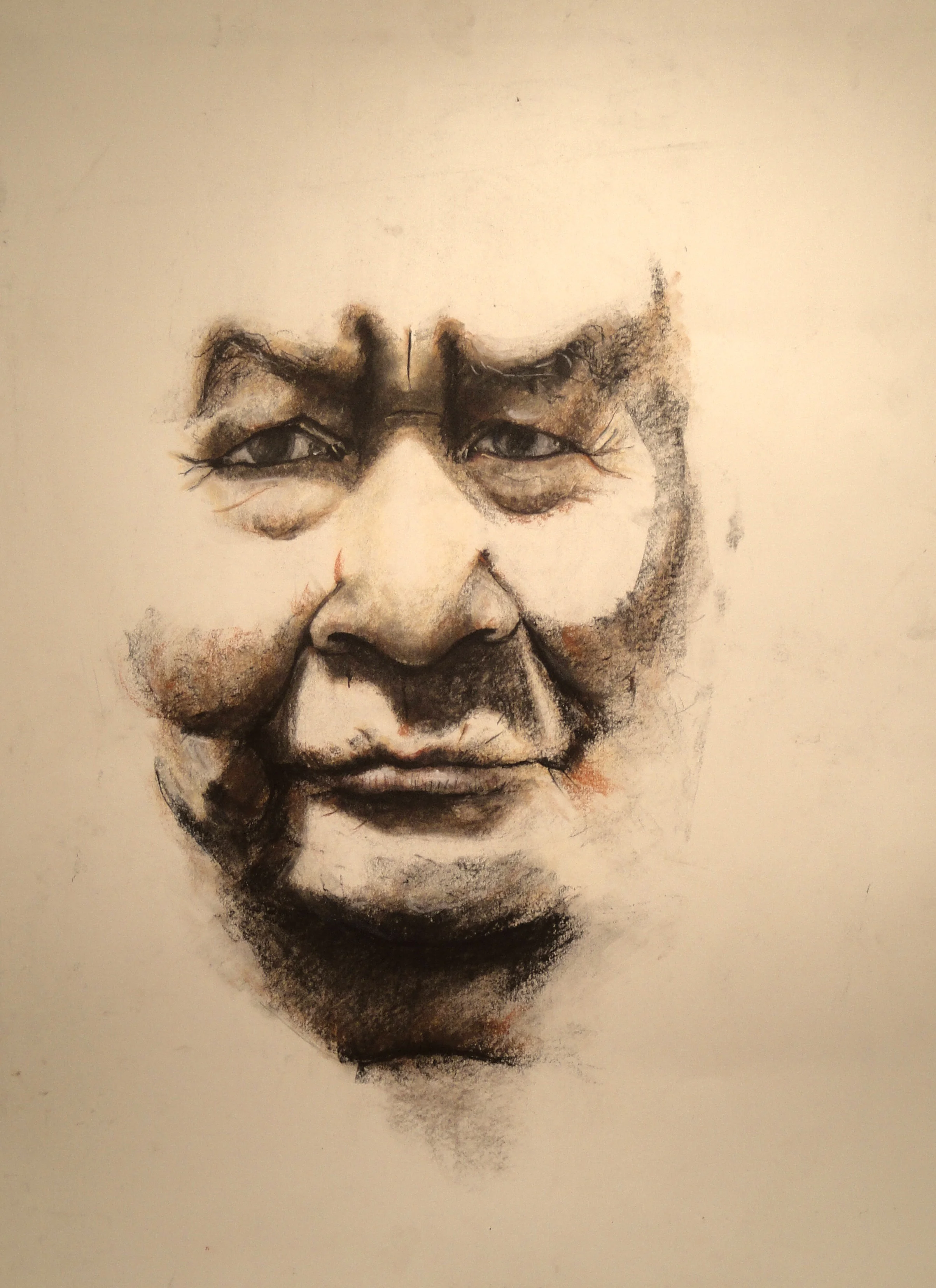

As we were observing the races taking place, the woman introduced me to her ninety-year-old father. He works with a linguistics professor once a week in the University of Victoria. His voice is recorded to “save the language” as he explains the meaning of certain words. This process is challenging because the deeper meaning of words in the Hul’qumi’num language cannot easily be translated into English. Nouns do not exist on their own but are connected to specific aspects of the environment in which they are created. When someone tells me salmon I think of fish, food, and the orange color, but an aboriginal person from the Quw’utsun’ tribe will relate this word to more complex meanings because of the particular importance of this animal in his life. Salmon will have a composite spiritual significance, have a specific artistic representation in totems, be personalized in stories, and refer to a specific period of the year that is attached with specific natural changes. To understand the Hul’qumi’num language, you need to understand the culture, the land, and the particular view world of the people that practice this language on a daily basis.

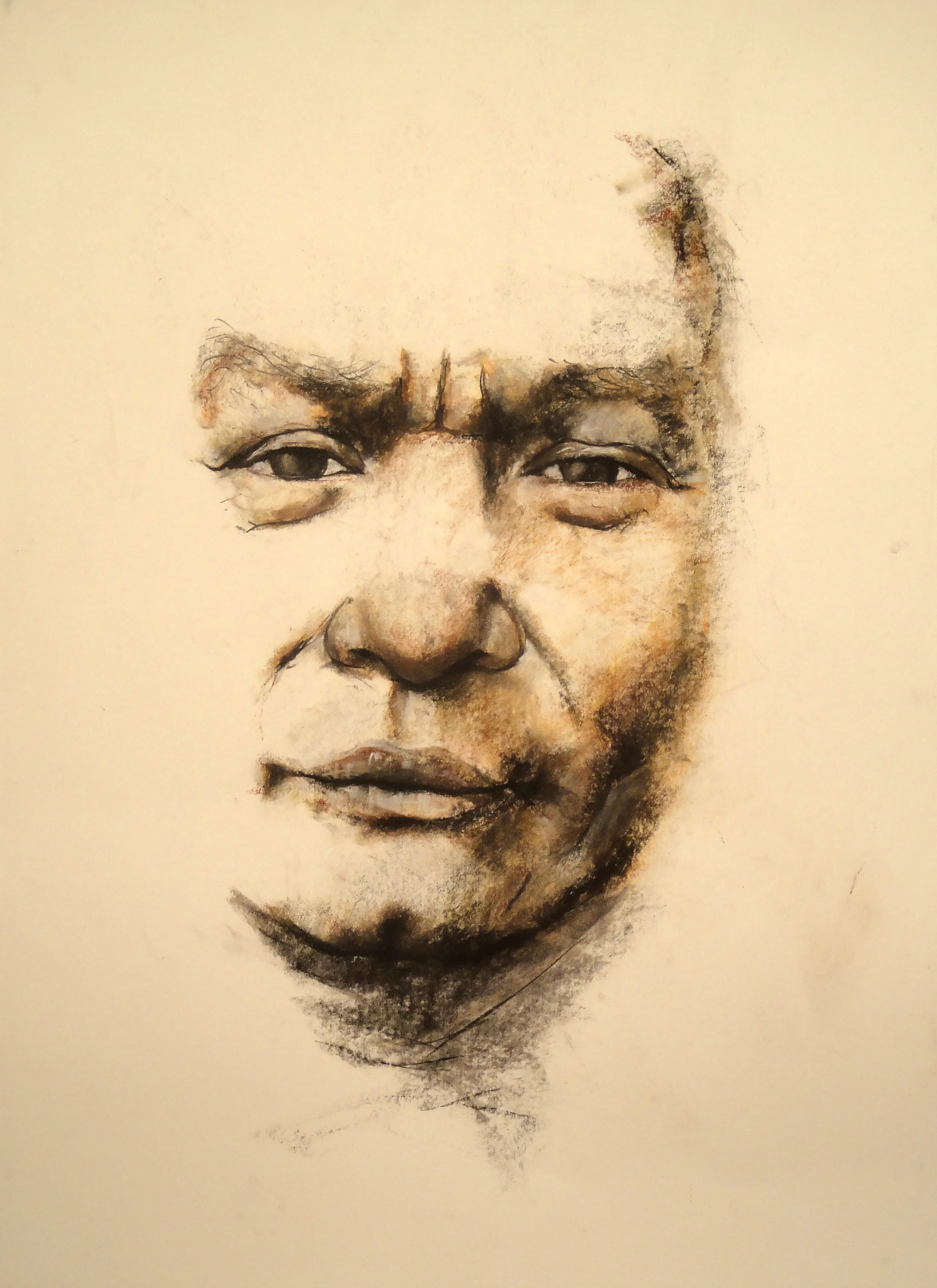

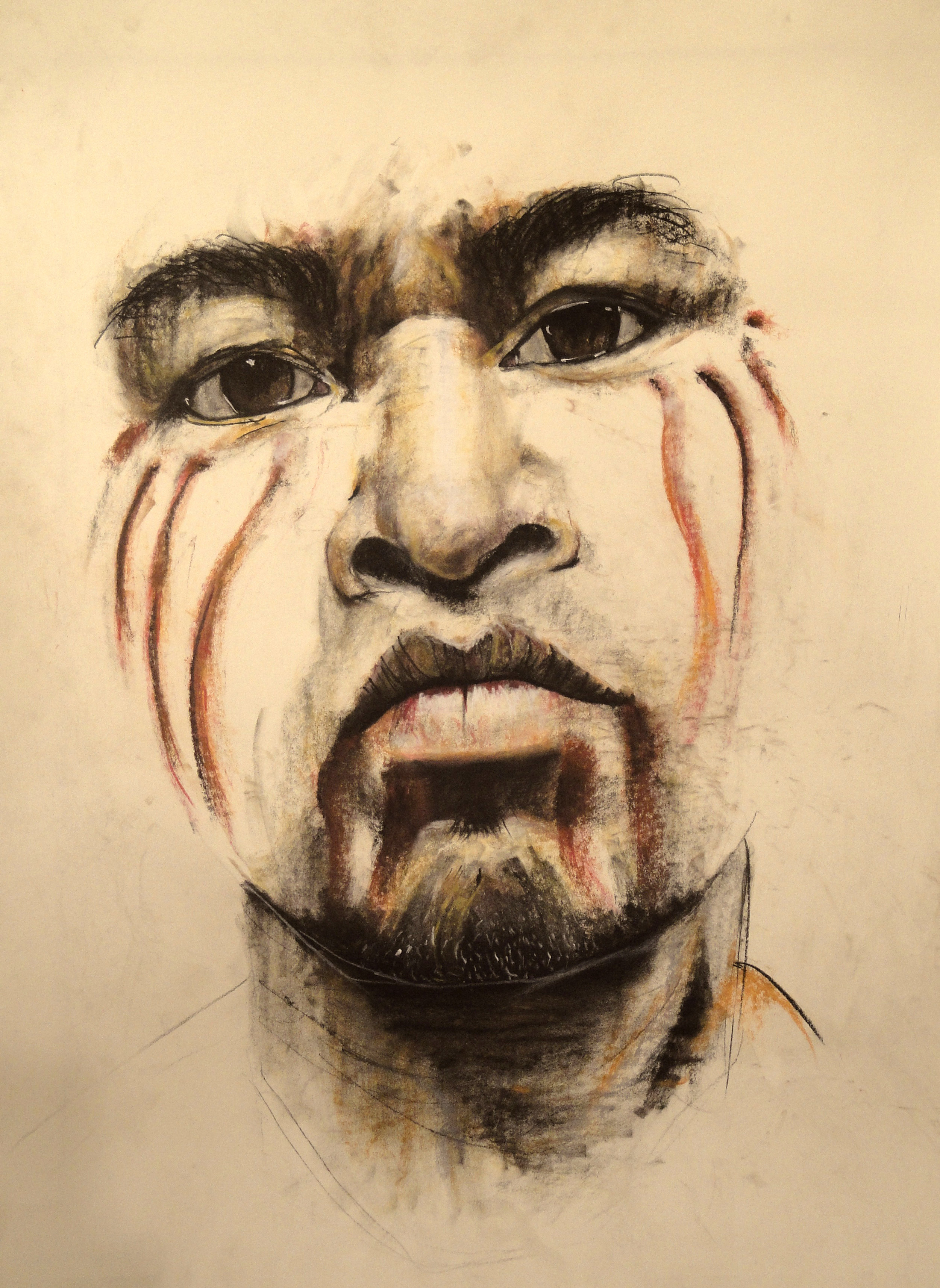

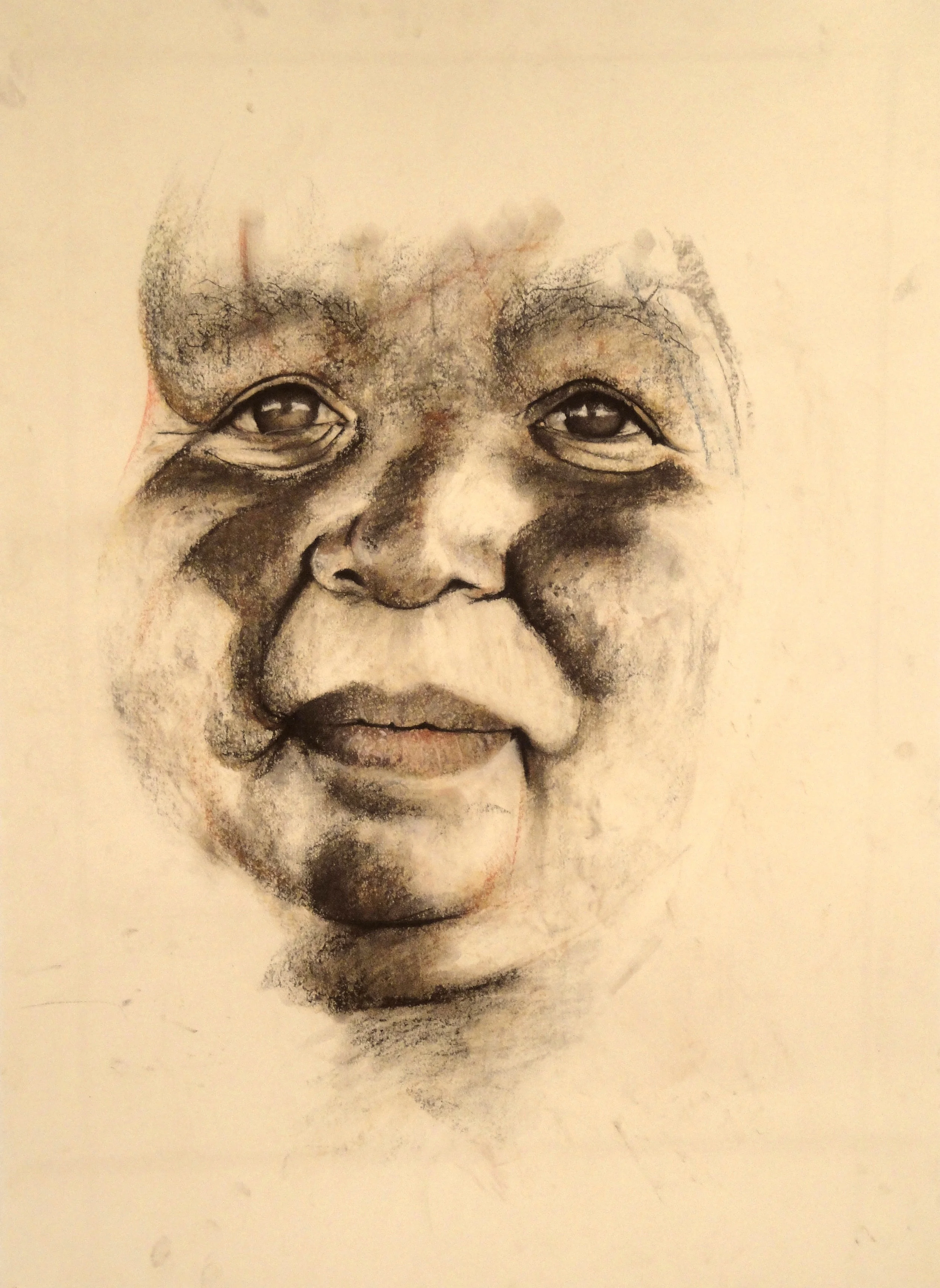

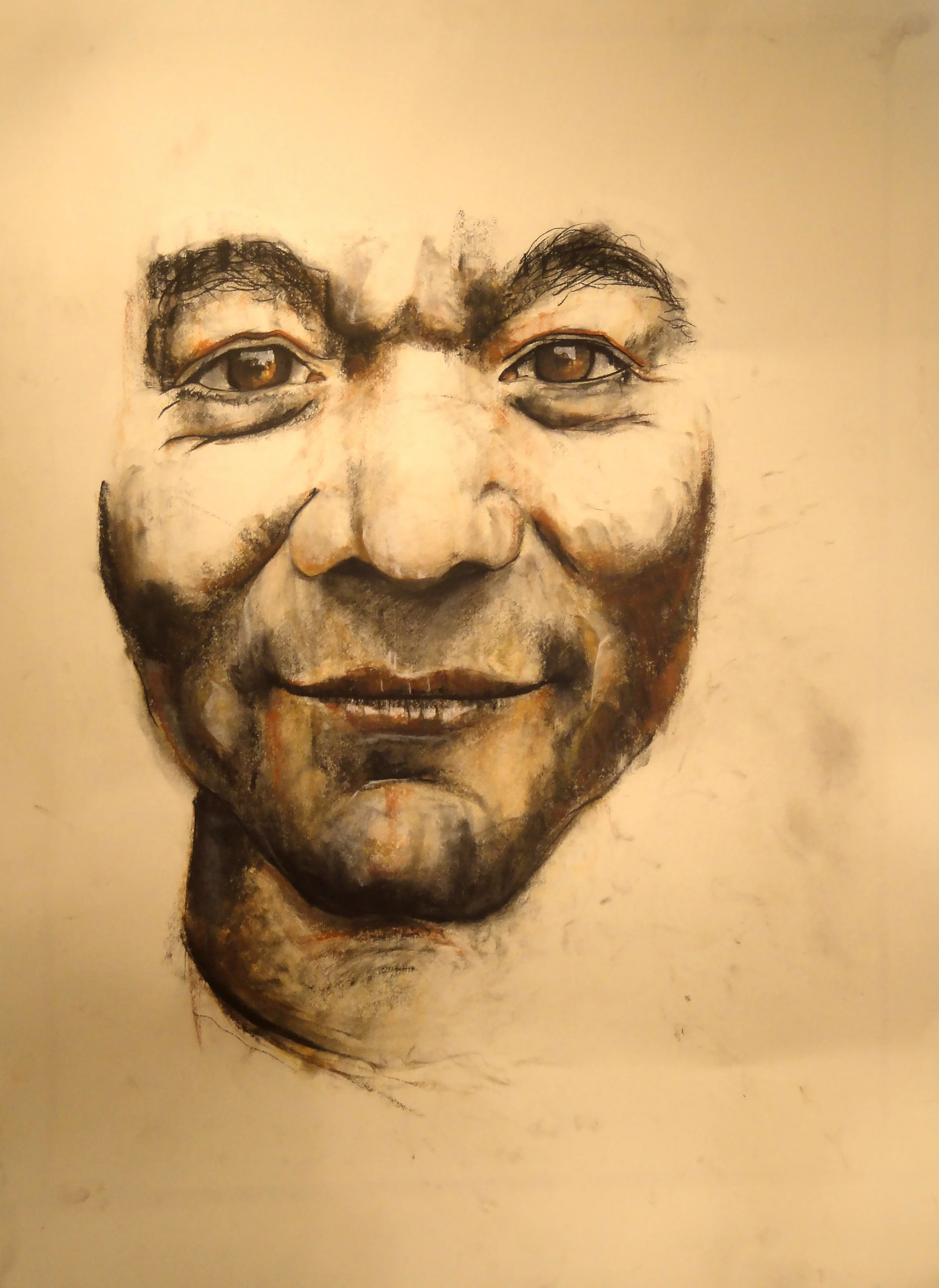

I spend most of June 2012 listening and observing the elders and younger generations of aboriginals from the Quw’utsun’ tribe on Vancouver Island. Never had I felt so different and foreign as I was on their reserve in the Cowichan Valley. During my interviews I felt like an insect scratching the soil of a new planet. Some of the tribe members told me their stories, some let me draw them, and some remained silent, but all of them have fostered in me a feeling of respect for their unique understanding of the world.

Throughout my stay I used art as bridge to overcome the fences that had grown between our two cultures. Europeans have been responsible in the extermination of aboriginals ever since they first landed on the coast of North America and the scars of the past have not yet healed. Studying in pastels how light reveals the curves of their faces while hearing their unique stories helped me to understand a few facets of their identities. Wisdom. Wholeness. Strength. But I also observed the fragility and anxiety that have formed because of the traumatizing experiences they have undergone.

As I drew the final portraits for each person two forces were interacting in my head and on the paper. On one hand was the essence of the person I was drawing. On the other hand was my own identity. The colors I chose to use, or the way I moved my hand as I drew are decisions born at the line where their identities join mine. Working on this line was a real balancing act. To often I was drawn into emphasizing how I saw them and interpreted them rather then truly letting their essence freely influencing the drawing that appeared on the paper.

As we move into the future, being aware of our own position on this line where the western culture met with the Quw’utsun culture is primordial. How willing are we to let their culture and worldview shaping ours? As I engaged with the people I quickly realized that if we want my generation and the youth generation of the Quw’utsun tribe to interact in equal terms in the future we need to engage in a new dialogue based on trust. And give them space to rebuild a sense of self-esteem and pride. Watching Hwientum openly talking to the cedar tree, in a language that was born from this land, is one of many moments that have shaped in me a sense of respect for their culture, and triggered a willingness to let their valuable worldview influencing mine.

Throughout this project I was insure and still am as to how much I took from them. Am I a thief who stole their stories and their faces as an inspiration for my art? Did they just felt like interesting objects a foreigner was drawing so that one-day their faces would hang still on the walls of his room? There is a value in the honesty of doubt behind those questions. As much as I emphasized on the difference and the line that separate us from them, we must not forget how similar we are.